Florine Stettheimer was a multifaceted modernist artist, theatrical designer, poet, and outspoken feminist. Along with her sisters, she hosted a groundbreaking avant-garde salon in New York. Stettheimer also created what’s believed to be the first feminist nude self-portrait and painted works exploring themes of race and sexual preference. Her art was exhibited in the U.S. and Europe during her lifetime, and after her death, her pieces were donated to American museums. Let’s delve deeper into the life of this talented woman on newyorkski.info.

Early Life and Education

Florine Stettheimer was born on August 19, 1871, in Rochester, New York. Her mother, Rosetta, came from a wealthy German-Jewish family. After marrying Joseph Stettheimer, she had five children, but her husband eventually left the family and moved to Australia. Rosetta raised her son and daughters alone. During the summers, the family would travel to Europe.

From childhood, Florine showed a talent for drawing. From 1881 to 1886, she studied at the Stuttgart Court Art Institute and also took private lessons from its director. While in Germany, Florine mastered German academic painting. In Europe, she eagerly visited art galleries and museums, immersing herself in art history. She studied the works of past masters, meticulously detailing her impressions in her diaries.

In 1892, Florine enrolled in the Art Students League of New York. There, she studied under Kenyon Cox, Harry Mowbray, and James Beckwith, all of whom worked in the French style. After graduation, she expertly painted realistic, traditional, academic, and nude portraits. Afterward, she returned to Europe, where she explored the paintings of her contemporaries and experimented with various styles.

She was particularly impressed by Serge Diaghilev’s “Ballets Russes,” which Florine saw in Paris in 1912. Inspired by them, she created the libretto, sets, and costumes for her own opera, “Orphee of the Four Arts,” though it was never staged.

The Stettheimer Sisters’ Salon

In 1914, Florine was in Bern when World War I suddenly broke out. She eventually managed to secure passage on a ship and return to her native New York. During this period, the artist decided to abandon traditional styles and create her own unique approach to express her feelings and experiences.

Florine Stettheimer and her sisters settled into an apartment in Manhattan and began hosting salons. They invited young expatriate artists like Marcel Duchamp and Albert Gleizes, as well as members of Alfred Stieglitz’s circle, such as Georgia O’Keeffe. Musicians, dancers, writers, poets, and other representatives of the avant-garde New York scene of the time also joined the salon.

What made the salon truly unique was that its participants didn’t need to hide their non-traditional sexual orientations. At the time, such relationships were illegal in New York, but the Stettheimer sisters paid no mind.

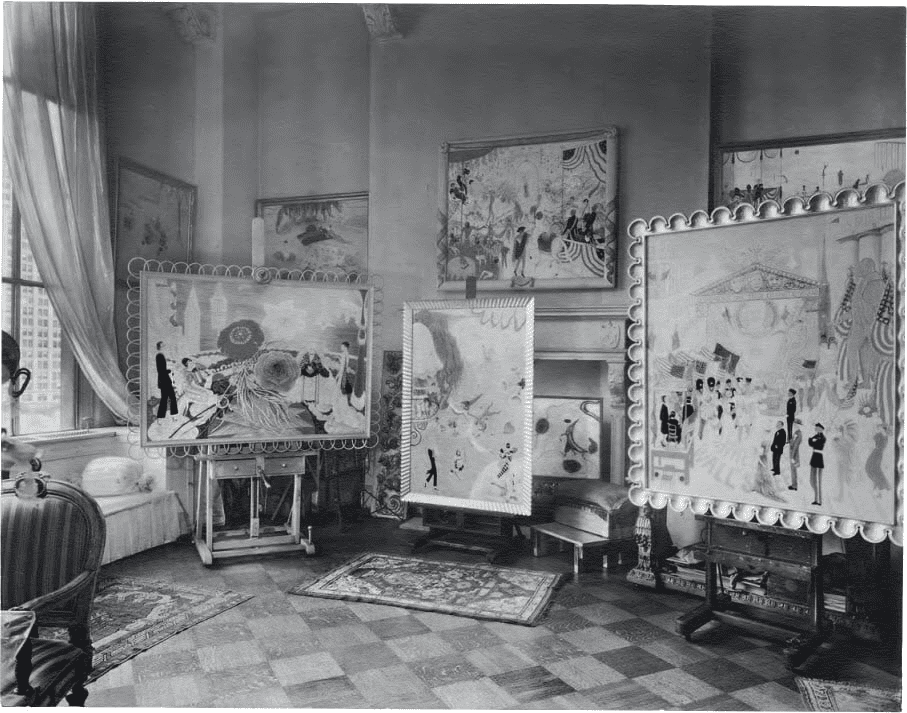

At their parties, Florine showcased her new paintings to guests. Her older sister Carrie prepared delicious cocktails and unusual dishes. In the summer, they often threw all-day parties, renting summer houses near the city. Florine also depicted these gatherings in several of her canvases.

Florine Stettheimer’s Paintings, Poetry, and Feminism

Throughout her life, Florine Stettheimer had only one solo exhibition. It took place in 1916 at Knoedler, thanks to Marie Sterner, the wife of artist Albert Sterner. This exhibition featured the artist’s early works, in which she often emulated Matisse. These paintings didn’t bring Florine popularity or find buyers.

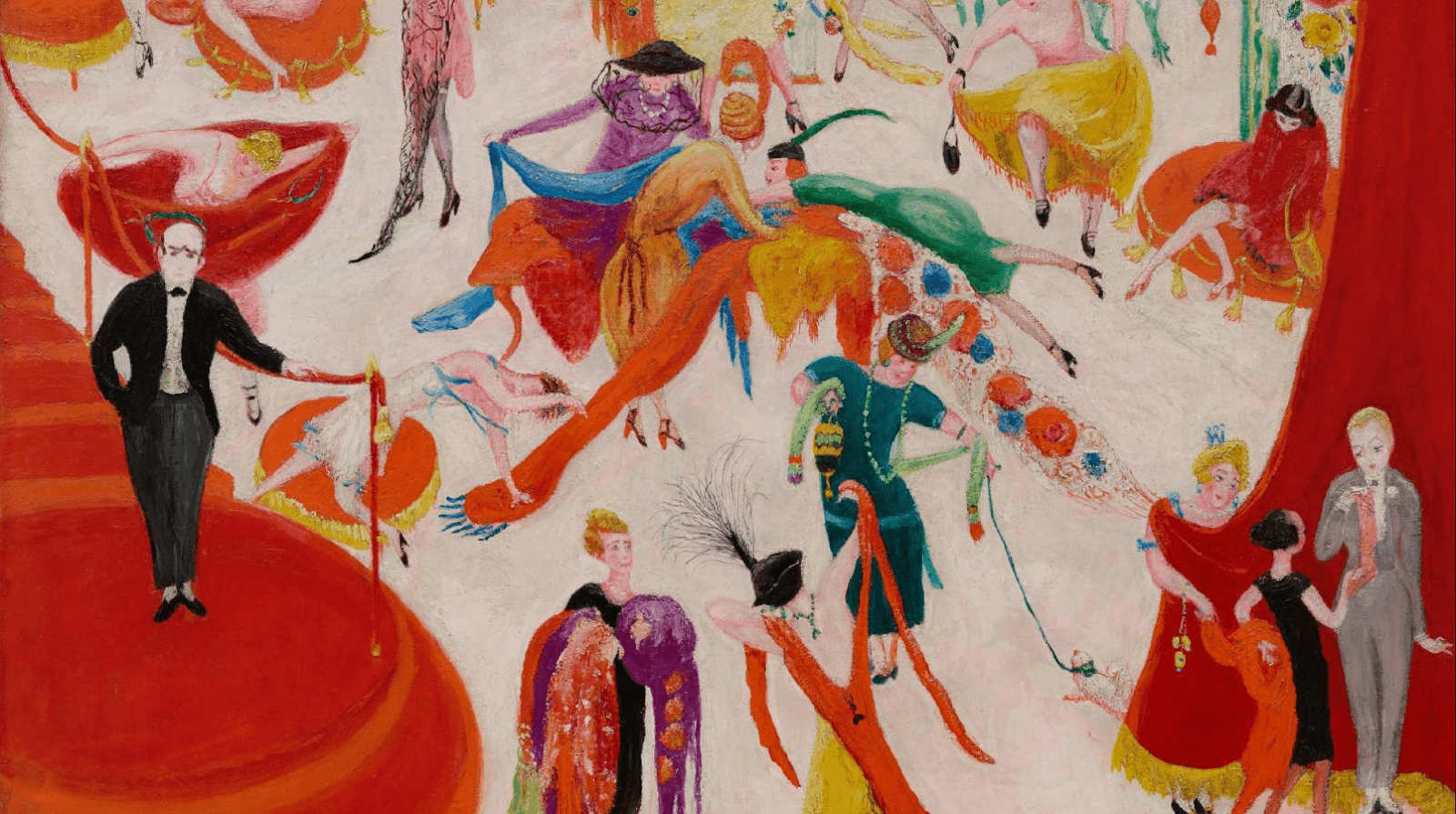

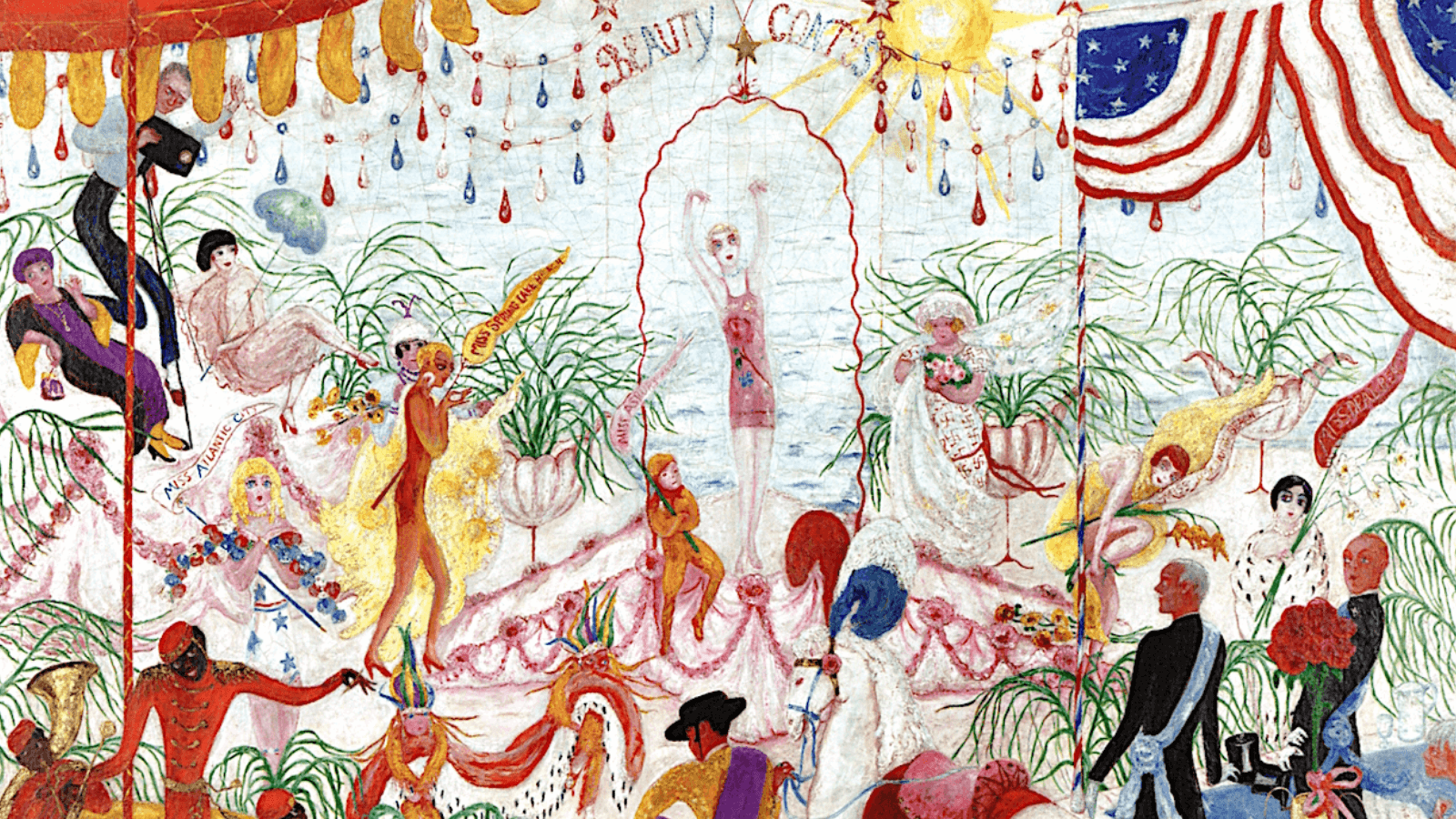

Subsequently, Stettheimer rejected traditional formalism and modernist abstraction, developing her own vibrant, theatrical style. Each of her later canvases transformed into a stage filled with family members, friends, and acquaintances. In her paintings, the artist used bright colors on a white background, adding many small, humorous touches. She also positioned figures around real prominent places and famous architectural landmarks, which she rendered with great accuracy.

Florine Stettheimer not only painted but also wrote poetry, though she didn’t circulate it widely. She jotted down lines on small scraps of paper, which, after her death, her sister Ettie collected and published for family and friends. This poetry is quite diverse—ranging from a light, childlike style to witty social criticism and satirical portraits of colleagues. Florine Stettheimer also wrote poems critiquing contemporary consumer culture and making biting remarks about the idea of marriage. This collection of poems was republished in 2010.

It’s also worth noting the artist’s progressive feminist views. Based on the content of her diaries, paintings, and poems, it can be concluded that the artist had romantic relationships with men in her younger years. Florine was fascinated by men and depicted these feelings in her art. At the same time, she was adamantly against marriage, believing it limited women and became an obstacle to creativity.

It’s known that Florine wore white pantaloons, as suffragists and feminists did. While in Europe, she actively studied feminist themes in art and was interested in the work of female performers. In 1896, Florine and her sisters attended the First International Feminist Congress in Paris.

In 1915, the artist painted a life-size nude self-portrait titled “The Model.” In the history of Western art of that time, this was a rare phenomenon and the first created by a woman. The self-portrait has a feminist character, as the artist holds a bouquet of flowers over frankly depicted pubic hair with a mocking expression.

Further developing feminist themes, Stettheimer created a series of works, such as “Spring Sale at Bendel’s” (1921). In it, she depicted wealthy women of various body types trying on clothes in an expensive department store. In another painting, the artist depicted nude women riding on floats and swimming in seashells. These works were highly unusual and progressive for their time, drawing even more attention to Florine Stettheimer’s art.

The Death of a Renowned Artist

Florine Stettheimer passed away on May 11, 1944, due to cancer in a New York hospital. She was cared for by her sisters Ettie and Carrie, as well as her lawyer Joseph Solomon. The artist requested that her body be cremated and her ashes scattered over the Hudson River, which was done.

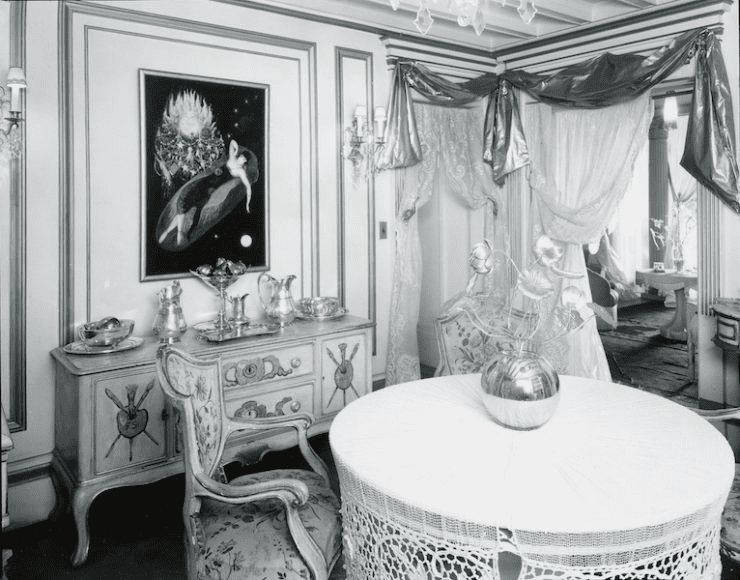

After the artist’s death, the Museum of Modern Art organized a retrospective exhibition of her works. This was the first time such an honor was bestowed upon a female artist. The exhibition then traveled to San Francisco and Chicago. Thus, the artist’s legacy was not lost, and art enthusiasts continued to be interested in her work and purchase her canvases.

Regarding her artistic legacy, Florine Stettheimer initially wanted an American museum to accept all of her works as a single collection. However, she revised this part of her will and asked her sisters to distribute the paintings to various museums across the U.S. Her lawyer handled this after her death, and thanks to his efforts, Florine Stettheimer’s canvases can now be seen in various parts of the country.